Contributing Author/s

Joseph Galiwango

Hip-Hop’s Critical Race Theory: Reflecting on 50 Years of Cultural Impact and Resistance

Hip-Hop’s Critical Race Theory: Reflecting on 50 Years of Cultural Impact and Resistance

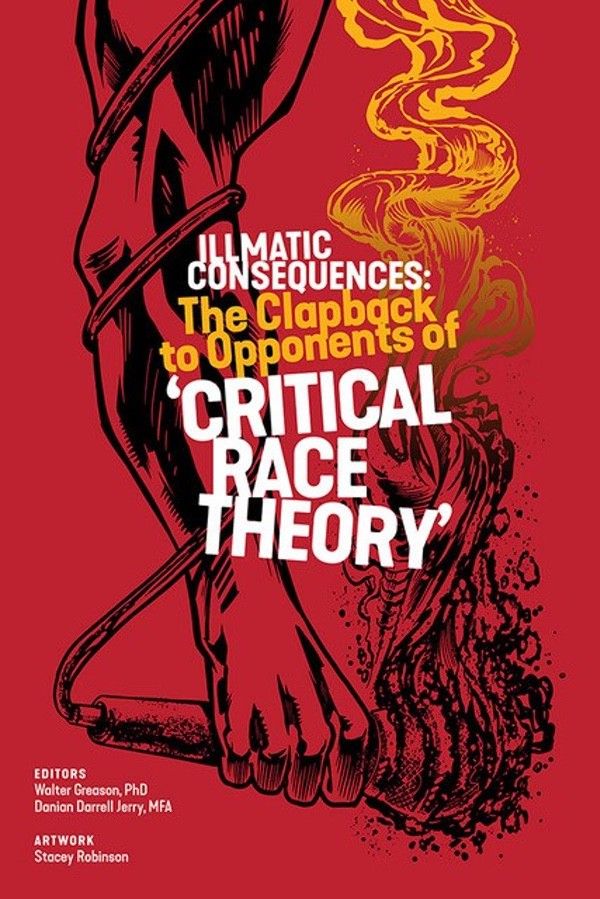

Book Review: Illmatic Consequences: ‘The Clapback to Opponents of Critical Race Theory’ – By Joseph Galiwago

Hip-hop culture turned 50 years old in 2023 and is in a state of multi-contextualism. Those who study the culture closely can identify many elements to critique, celebrate, exploit, and emulate simultaneously.

Andre 3000, one-half of the legendary Atlanta rap group Outkast, released an instrumental album in November 2023. He is regarded by many as one of the greatest rap lyricists in hip-hop. Andre 3000 is grown, and he’s decided to leave lyrics out of his current music offering. In interviews, he explained that he feels he has nothing to rap about and chooses to play his wind instruments. Many fans celebrated his independence, while others wanted more rapping. Some of Andre’s earliest lyrics were in the spirit of Black people speaking painful truths about society. ‘On In Due Time’, by Outkast song featuring Cee-Lo, Andre shows off his social critique by clarifying his purpose for rapping,

“You wonder why I spit the truth and not to make no dough /

To make a difference ‘fore this motherf–ker up and blow/

In pieces/

I could think of many reasons/

Only when shit is going bad, you want to holla Jesus/

F–k a pledge allegiance,/

they got my knuckles bleedin’ From crawling/

Got these ni–as thinkin’ they really ballin’ When they isn’t/

Don’t take my word, there’s ni–as off in prison That will tell you/

That’s locked up for long time and won’t sell you no flex”

Mainstream America has always associated rappers and their lyrical content with criminality, which glosses over the painful reality of any criminality that might grow. Powerful futures in the current political climate have deemed critical analysis of society, ‘wokeness”, and critical race theory to be a threat that must be eliminated. The chapter by Ronda Racha Penrice, titled ‘Hip-Hop Represented Long Before Critical Race Theory Became a Conservative Rallying Point’, reflects how rap music has been fearless and brilliant in its critique of American systemic racism and oppression by telling the truth about our society.

At one point in the chapter, Penrice describes rappers using their art form to document pain and resistance to the oppression in American communities through their music as a “the mission”. When one is on a mission, the conviction to complete that mission comes from somewhere deep inside. When one is on a mission, accomplishment equals survival. Penrice takes readers into this mission by analyzing the lives of Nas and other artists. She starts with Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, who released “The Message”, arguably the first rap song that spoke directly about dire conditions in Black America.

The song, released in 1982, describes underdeveloped neighborhoods in New York using detail that shifted the function of rap music from partying to also speaking truth to power. In the song, the lead rapper, Rapper Melle Mel: Delivering ‘The Message’ – NPR , says

| “‘A child is born with no state of mind/ Blind to the ways of mankind/ God is smiling on you but he’s frowning to/ Because only God knows what you’ll go through/ You’ll live in the ghetto living second rate/ and your eyes will sing a song of deep hate/ the places you live the place you stay, looks like one great big alleyway.” “ |

Nas would later refine this style of rap with a sharp rawness that made him a legend from the genesis of his career. In his song New York State of Mind, released in 1993, his descriptive style put listeners inside the Jungle that was described earlier in The Message –

| “It’s like the game aint the same / You got younger n–as pulling the triggers bringing fame to their name / And claim some corners/ Crews without guns are goners/ In broad daylight, stick-up kids, they run up on us.“ |

Penrice structures her chapter by describing the tradition of the clap back through analysis of rappers who have used their music to educate their listeners about institutional, ideological, and interpersonal racism, which has devastated their communities across America.

The work of Nas is closely examined and paired with hip-hop culture’s response to the many killings of unarmed Black Americans by police following the murder of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman, who was acquitted of all charges. Sandra Bland, Philando Castile, Mike Brown, Breonna Taylor, and Eric Garner, among others, have been honored through the tradition of rap songs critiquing the brutality of racial injustice in America. This tradition, Penrice brilliantly clarifies, is an example of hip-hop offering its brand of critical race theory to its young audience.

Another Nas song left out of the chapter is “We Will Survive” from his 1999 album “I Am.” In the song, Nas has a conversation with the recently murdered Notorious BIG and Tupac while comparing the tragedies of his genre to those of his elders. “I wonder what the Commodores went through on tour/ Did Smokey Robinson have to shoot his way out of war?”

Songs like this remind us why hip-hop’s brand of critical race theory has an authenticity that threatens capitalistic mainstream racist ideas. Penrice explores how hip-hop’s brand of critical race theory is part of a Black American musical lineage that follows earlier genres such as The Blues, Gospel, and Soul. In these genres, songs about tragedy visited upon the downtrodden are addressed in a way that moves the listener and evokes sadness, l hope, and the desire for more. The words and sounds come from deep down inside. This is the spirit of the mission Penrice is describing in her chapter.

Penrice has created a critical race theory playlist for the reader. Each song in this list critiques American oppression and systemic racism unique to the rappers’ voice and vision. The songs are positioned to highlight the unsung tradition of Black voices who critically reflect on the conditions of their communities. Penrice references the seminal text, The Mis-education of the Negro by Carter G Woodson, as an inspiration for Lauryn Hill’s classic debut album, The MisEducation of Lauryn Hill. Some of Lauryn Hill’s vocal styles arguably can be inspired by Jazz and Blues singers like Sarah Vaugh and Billy Holiday, who also used their artistic brilliance to critique the world they lived in. This tradition of analyzing racism in America from an authentic Black perspective is where Critical Race Theory (C.R.T.), the academic theory developed to address systemic racial injustice, developed by Derrick Bell and his peers, comes from.

Penrice is intentional about using Nas’s “Untitled’ album to go in-depth about his commentary on the history of anti-Black racism in mainstream entertainment and society at large. Other selections made by Penrice honor rappers from hip-hop’s golden age, such as Public Enemy, Queen Latifah, Boogie Down Productions, and NWA, to more diverse artists like Dead Prez, Lupe Fiasco, Young Jezzy, Rapsody, and Lil Baby.

Penrice analyses artists who have come of age while the world reacted to the killings of Travon Martin, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, and the like while Barack Obama was president of the United States. Penrice gives equal validity to the clap back from the more contemporary artists’ compared to their older peers from past eras. She allows the reader to experience the relentlessness of the mission and the clap back that rappers have made during hip-hop’s 50 years. She puts this mission in context by stating that “Hip-hop, even with its varied styles and approaches, has been one of the most consistent challengers of the erasure of Black American history and culture.”

After 50 years of hip-hop, Penrice’s style of reflection reaffirms the original conviction of the culture: amplifying marginalized perspectives so that the people can regain power. Illmatic Consequences: The Clapback to Opponents of ‘Critical Race Theory, an essential read for anyone who wants to reconnect with the brilliance of the culture.

Disclaimer:

Article Tags

Related Title/s

Contributing Author/s