Sheba Pace, Ph.D.

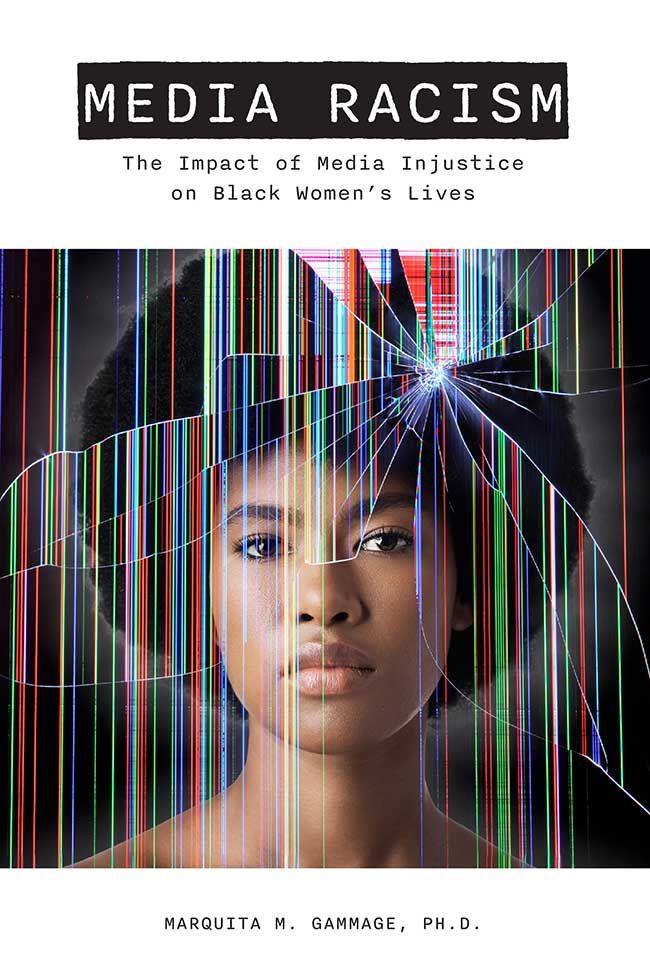

Racism in the Media: How 'Queen & Slim' Challenges Black Activist Narratives

Racism in the Media: How 'Queen & Slim' Challenges Black Activist Narratives

During most historical Black activist movements, many Black men and women attempted to assist each other with fighting against various forms of socioeconomic oppression. However, the film Queen & Slim (Matsoukas et al., 2019) counters previous nonfictional narrative accounts by placing Black men and women in adversarial positions in a present-day Black activist movement. Hollywood filmmakers’ conscious and unconscious role in using entertainment to sabotage Black heterosexual relationships and their political activism cannot be minimized or dismissed. Specifically, Ed Guerrero’s (1983) groundbreaking Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film, states,

|

"in these films we can most readily see both the industry’s ideological power to shape the audience’s conceptions of race and its mediation of the audience’s racial and social attitude" (p. 4). |

It is evident that the film Queen & Slim serves as racist propaganda. For approximately two hours, viewers are indoctrinated with stereotypes of the unworthy Black woman, man, and community, exemplifying media racism.

At the start of the film, viewers witness the main characters, Queen and Slim, eating dinner during their first date. This meal provides an opportunity for individuals to become acquainted while obtaining physical nourishment for the body and satisfying an appetite. However, the social interaction between Queen and Slim is emotionally and mentally unhealthy and exhaustive. Although this is an introductory dinner, the two individuals quickly develop an understanding about each other’s ideologies. Queen’s values place her in the antagonist position, and Slim’s beliefs put him in the role of the protagonist. In this instance, the filmmaker creates a female character who rejects Slim while simultaneously disregarding the Black community’s moral codes and practices, such as womanism. According to Alice Walker (1983), womanists are men and women who are dedicated to the longevity and advancement of communities and the entire human race. It is important to note womanism is different from widely held stances on feminism, which has promoted sociopolitical individuality instead of community upliftment. An exaggerated sense of self-importance can contribute to the demise of a person and their race.

Queen’s demeanor at dinner with Slim foreshadows her destructive behavior throughout the film; she is credited with annihilating the self, men, and families. During the meal with Slim, which is supposed to be a pleasant experience, Queen creates a hostile environment. She responds to Slim’s genuine romantic interest and appropriate social conversations with deadly force. According to David Pilgrim (2023), Queen’s conduct is a representation of the sapphire caricature. Pilgrim’s pivotal article expounds on the characteristics of the vicious Black woman. The Sapphire Caricature (Pilgrim, 2023) explains that “although African American men are her primary targets, she has venom for anyone who insults or disrespects her.” It is reasonable to believe that Queen has noble intentions, so one understands that she is an individual, and each person responds differently to life challenges, such as emotional pain, financial loss, and oppressive socioeconomic conditions. Queen may be unaware that she is embodying the sapphire caricature, which is the modern-day strong Black woman stereotype. A plethora of studies assert that Queen’s experiences with various forms of trauma resulted in her heightened defense mechanism and her combative posture.

Queen perceives all people, actions, and words as a threat, and this perception causes her to be extremely protective of the self, treat others with aggression, and, if necessary, physically destroy people. At the beginning of the film, it can be assumed that Queen’s reaction to Slim is a part of the Black female sassy tradition; this is a protection guard that consists of women employing words and wit to protect themselves from various forms of male abuse, insults, and mockery. For instance, Joanne M. Braxton’s (1989) revolutionary Black Women Writing Autobiography: A Tradition Within a Tradition traces the logical cause and effect in circumstances that lead to female protagonists’ attacks against men. Braxton observes that Black women who have suffered long-term exploitation and violation in their relationships eventually develop the courage to challenge the physical and emotional abuse (pp. 156–158). However, it is difficult to offer a rationale for Queen’s cruelty toward Slim, a man who is calm, sensitive, and balanced.

After a final determination is made about Queen’s disposition, the viewer patiently waits for her to display redeeming qualities. One way she can accomplish this goal is by making amends with Slim, who is the victim of Queen’s abusive treatment. However, she continues to practice antisocial behavior when she fails to humanize herself by apologizing to Slim for her misunderstandings and unwarranted attacks against him. Queen attempts to annihilate him for his restaurant choice. Although the anger she lashes out at him is a result of a culmination of psychological and emotional issues associated with her conscious or unconscious embrace of the sapphire caricature, her treatment is extremely violent, and the viewer cannot justify and accept Queen’s ill treatment of Slim. As a result, she is an unsympathetic character, which causes viewers to lend all their support to Slim.

In continuing to examine the opposition in the Black female identity and the Black male and female romantic relationship, it is concluded that the cause of Slim’s demise is his association with Queen, who is dysfunctional. This unhealthy interaction between Queen and Slim is presented as an irrational hierarchy. For instance, Queen uses education and her profession as power. She is an expert at weaponizing language, and she employs these competencies to dominate, control, and reduce others. Further, Queen holds a title that is unbefitting to her. The dictionary defines the title queen as a chief or controlling woman in an organization or social group. bell hooks (1981) argues,

|

"the term matriarch implies the existence of a social order in which women exercise social and political power, a state which in no way resembles the condition of black women or all women in American society" (p. 72). |

Not only do the matriarch and queen positions encompass power, but they should coexist with grace, humility, dignity, strategy, and wisdom. In this film, the female character is the antithesis of a stately female figure. Queen, who is a tragic character with many undesirable qualities, reduces Slim. Queen emotionally, spiritually, and mentally destroys Slim, and she is responsible for escalating the police incident and causing Slim to be killed senselessly at the end of the film.

Slim does not deserve to be murdered because he has the values, humanity, civility, decency, and intellect that exhibit love of self, family, and the Black community. Moreover, he depicts an understanding of how to remain safe and provide security to others. Contrarily, Slim does not hold the title of king; his name, persona, demeanor, intellect, and values must make him small in comparison to Queen. With all of Queen’s professional and educational accomplishments, she is a failure. She is unable to recognize the sublime in the human experience, and this character flaw fuels her illogical oppositional patterns. Unlike Slim, Queen does not have a moral compass; she is beyond reproach, and equally as important, her language and actions are reckless, which prove to be detrimental to the Black community and its movements, reinforcing the theme of racism in the media.

In closing, evidence from the film shows that Queen demonstrates misandrist and misogynist behavior. She uses her influence to abuse men, and she perpetuates negative stereotypes about Black women. Consequently, the film upholds the racists’ generalizations of the unsuccessful Black woman, man, and community. There is diversity in the Black experience, and it is important to evaluate the treatment of Black heterosexual romantic relationships and activism in past literary and film works in order to scrutinize the continuums and divergences in these female and male characters. More analyses that expose healthy interactions between Black men and women will reveal how both genders are complementary in their service as family and community protectors, caretakers, and activists.

References

Braxton, J. M. (1989). Black Women Writing Autobiography: A Tradition within a Tradition. Temple University Press.

Guerrero, E. (1983). Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film. Temple University Press.

hooks, b. (1981). Ain’t I A Woman: Black Women and Feminism. South End Press.

Matsoukas, M. (Director), Waithe, L., & Frey, J. (Writers). (2019). Queen & Slim [Film]. Makeready; De La Revolución Films; Hillman Grad; 3Blackdot; BRON Studios; Creative Wealth Media Finance; Entertainment One.

Pilgrim, D. (2023). The sapphire caricature. Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia. [Link](https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/antiblack/sapphire.htm)

Walker, A. (1983). In Search of Our mothers’ Gardens. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Disclaimer:

Article Tags

Related Title/s

Sheba Pace, Ph.D.